Learning Go: CPU Profiling

In an effort to learn about the Go programming language (golang) and tools, let's create a simple program, profile it, and try to make it go fast.

How about a game?

The Computer Language Benchmarks Game is a fun source of simple program requirements. Their k-nucleotide benchmark appears to be one on which Go has not performed the best, losing to 15 other languages at the time I first started playing the Benchmarks Game. To make this exercise fun, we'll use an adaptation of that benchmark — not exactly that benchmark, but a simple imitation of it, close enough that whatever we learn here can also help us there. These are our requirements:

Read a DNA sequence from standard input. It will look something like this:

CCCATAACTACAATAGTCGGCAATCTTTTATTACCCAGAACTAACGTTTTTATTTCCCGG TACGTATCACATTAATCTTAATTTAATGCGTGAGAGTAACGATGAACGAAAGTTATTTAT GTTTAAGCCGCTTCTTGAGAATACAGATTACTGTTAGAATGAAGGCATCATAACTAGAAC ACCAACGCGCACCTCGCACATTACTCTAATAGTAGCTTTATTCAGTTTAATATAGACAGT . . .Count up all the different subsequences of a given length.

Print the count for a specific subsequence, just to make sure everything works.

The full input will be about 120 MB, the same input that is used in the

Benchmarks Game. We'll count up all subsequences of length 18 and then print

the count for GGTATTTTAATTTATAGT.

Round 1

Here is a straightforward implementation, with one function to read the input, another function to count all subsequences of a given length, and a main function.

package main

import (

"bufio"

"bytes"

"fmt"

"os"

)

func main() {

sequence := "GGTATTTTAATTTATAGT"

dna := read()

counts := count(dna, len(sequence))

fmt.Printf("%v\t%v\n", counts[sequence], sequence)

}

func read() []byte {

var buf bytes.Buffer

scanner := bufio.NewScanner(os.Stdin)

for scanner.Scan() {

buf.WriteString(scanner.Text())

}

return buf.Bytes()

}

func count(dna []byte, length int) map[string]int {

counts := make(map[string]int)

for i := 0; i < len(dna)-length+1; i++ {

counts[string(dna[i:i+length])]++

}

return counts

}

It takes about 23.9 seconds to run on my machine and finds 893 instances of the

specified subsequence. In order to see where the program spends these 23.9

seconds, we can add a bit of code to enable the CPU profiler. With

runtime/pprof added to the imports and the following added to the beginning

of main, building and running the program again saves a profile to

round_1.prof.

f, _ := os.Create("round_1.prof")

pprof.StartCPUProfile(f)

defer pprof.StopCPUProfile()

The pprof tool can be used to analyze the resulting profile. Two of the most

useful pprof features are the top command and the ability to export

callgraph images.

The top command shows a list of the most expensive functions:

$ go tool pprof round_1_prof round_1.prof

Entering interactive mode (type "help" for commands)

(pprof) top 8

23230ms of 27200ms total (85.40%)

Dropped 65 nodes (cum <= 136ms)

Showing top 8 nodes out of 36 (cum >= 4260ms)

flat flat% sum% cum cum%

11330ms 41.65% 41.65% 14520ms 53.38% runtime.mapaccess1_faststr

2730ms 10.04% 51.69% 3560ms 13.09% runtime.mallocgc

2110ms 7.76% 59.45% 2110ms 7.76% runtime.memeqbody

2060ms 7.57% 67.02% 2060ms 7.57% runtime.aeshashbody

1800ms 6.62% 73.64% 4850ms 17.83% runtime.mapassign1

1410ms 5.18% 78.82% 26420ms 97.13% main.count

1140ms 4.19% 83.01% 1140ms 4.19% runtime.memmove

650ms 2.39% 85.40% 4260ms 15.66% runtime.rawstring

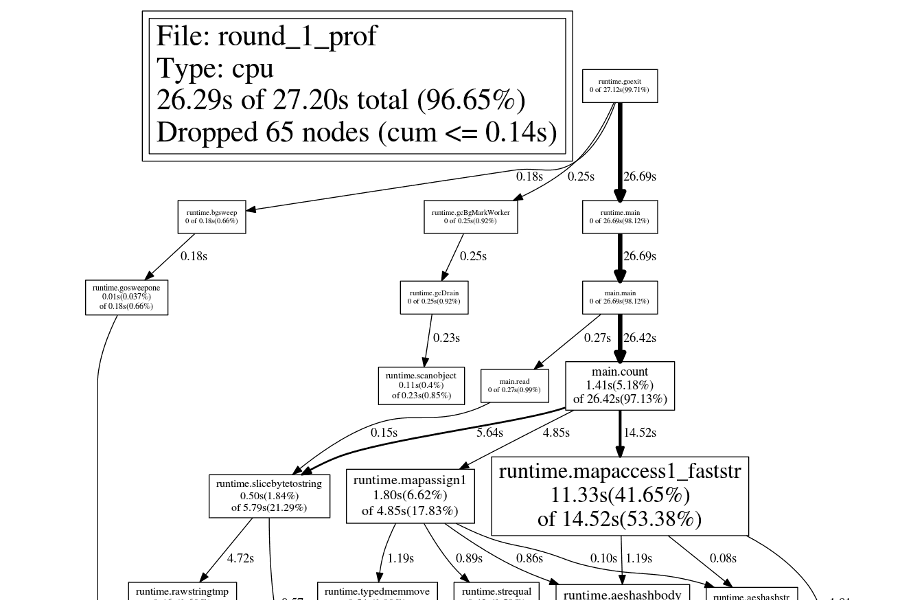

The png command creates a callgraph image, with each node sized according to

the function's cost:

$ go tool pprof -png round_1_prof round_1.prof > round_1.png

Round 2: Pointers

Let's ignore the most expensive functions for now and instead focus on

runtime.mapassign1, since this will provide an easy optimization. In Go, map

elements cannot be modified, so every

counts[string(dna[i:i+length])]++

is a map access, then an increment, and then a map assign. On each iteration

through the loop, we pay for two map operations. This can quickly be verified

with another pprof command, disasm, which shows the Go assembly for all

functions that match the command's argument.

(pprof) disasm count

.

.

.

40ms 12s 40163f: CALL runtime.mapaccess1_faststr(SB)

. . 401644: MOVQ 0x20(SP), BX

80ms 80ms 401649: MOVQ 0(BX), BX

780ms 780ms 40164c: INCQ BX

20ms 20ms 40164f: MOVQ BX, 0x38(SP)

10ms 10ms 401654: LEAQ 0xc42a5(IP), BX

. . 40165b: MOVQ BX, 0(SP)

10ms 10ms 40165f: MOVQ 0x40(SP), BX

. . 401664: MOVQ BX, 0x8(SP)

30ms 30ms 401669: LEAQ 0x48(SP), BX

. . 40166e: MOVQ BX, 0x10(SP)

30ms 30ms 401673: LEAQ 0x38(SP), BX

. . 401678: MOVQ BX, 0x18(SP)

20ms 5.10s 40167d: CALL runtime.mapassign1(SB)

.

.

.

We can avoid almost all the map assigns by storing the counts themselves

outside the map and storing pointers to the counts in the map. Then

runtime.mapassign1 will only be called when a new subsequence is encountered.

Here is the resulting code:

package main

import (

"bufio"

"bytes"

"fmt"

"os"

)

func main() {

sequence := "GGTATTTTAATTTATAGT"

dna := read()

counts := count(dna, len(sequence))

seqCount := 0

p, ok := counts[sequence]

if ok {

seqCount = *p

}

fmt.Printf("%v\t%v\n", seqCount, sequence)

}

func read() []byte {

var buf bytes.Buffer

scanner := bufio.NewScanner(os.Stdin)

for scanner.Scan() {

buf.WriteString(scanner.Text())

}

return buf.Bytes()

}

func count(dna []byte, length int) map[string]*int {

counts := make(map[string]*int)

for i := 0; i < len(dna)-length+1; i++ {

key := string(dna[i : i+length])

p, ok := counts[key]

if !ok {

p = new(int)

counts[key] = p

}

*p++

}

return counts

}

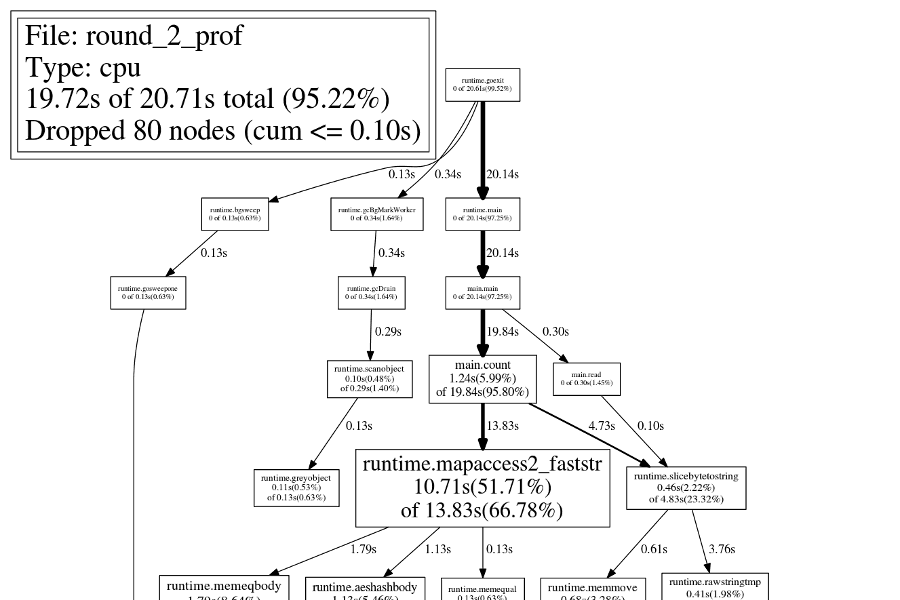

This version runs in about 19.2 seconds, and if we look at the callgraph now,

runtime.mapassign1 is nowhere to be found! Of course, time is still spent

running that function, but so little time that it is not shown by default.

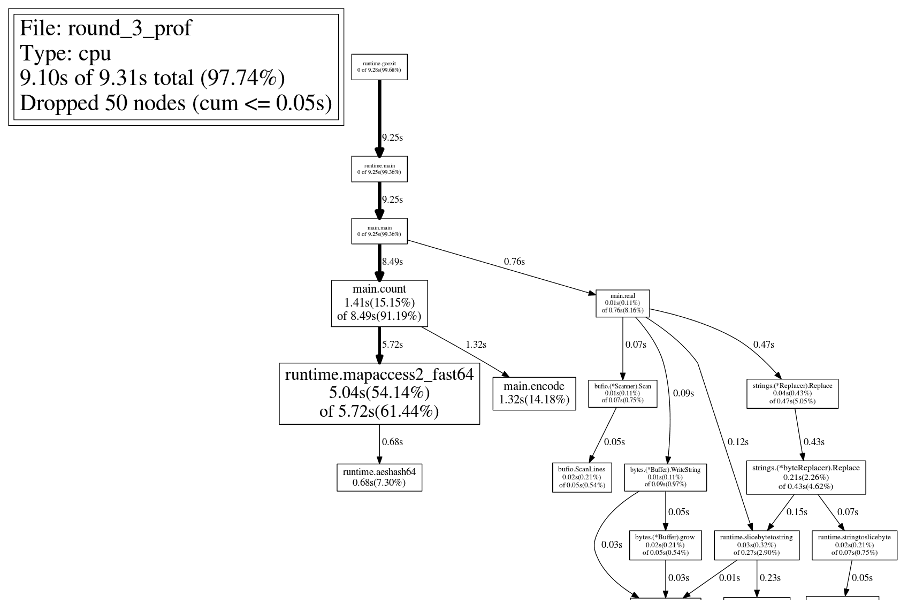

Round 3: Key Encoding

Next we turn to the most obvious node in the callgraph, the gigantic

runtime.mapaccess2_faststr in the middle. How to improve this? So far, we are

using strings as our map keys. But what are we really storing there?

Subsequences. The subsequences happen to be encoded as strings, but they don't

have to be. A more compact encoding might help.

There are four possible elements in these subsequences, so each element can be represented in two bits. Here's one possible encoding:

A: 00b

C: 01b

G: 10b

T: 11b

The subsequences of interest contain 18 elements, so a type with at least 36

bits is required. A 64-bit integer will work. For example, the

GGTATTTTAATTTATAGT subsequence can be represented as follows:

G G T A T T T T A A T T T A T A G T

101011001111111100001111110011001011b = 46438350027

Let's do part of the encoding change (mapping the letters to numbers) while the input is scanned in, and do the other part (converting each subsequence to a single integer) while the map is populated. Here is the result, which runs in about 8.7 seconds:

package main

import (

"bufio"

"bytes"

"fmt"

"os"

"strings"

)

var toNum = strings.NewReplacer(

"A", string(0),

"C", string(1),

"G", string(2),

"T", string(3),

)

func main() {

sequence := "GGTATTTTAATTTATAGT"

dna := read()

counts := count(dna, len(sequence))

seqCount := 0

p, ok := counts[encode([]byte(toNum.Replace(sequence)))]

if ok {

seqCount = *p

}

fmt.Printf("%v\t%v\n", seqCount, sequence)

}

func read() []byte {

var buf bytes.Buffer

scanner := bufio.NewScanner(os.Stdin)

for scanner.Scan() {

buf.WriteString(toNum.Replace(scanner.Text()))

}

return buf.Bytes()

}

func count(dna []byte, length int) map[uint64]*int {

counts := make(map[uint64]*int)

for i := 0; i < len(dna)-length+1; i++ {

key := encode(dna[i : i+length])

p, ok := counts[key]

if !ok {

p = new(int)

counts[key] = p

}

*p++

}

return counts

}

func encode(sequence []byte) uint64 {

var num uint64

for _, char := range sequence {

num = (num << 2) | uint64(char)

}

return num

}

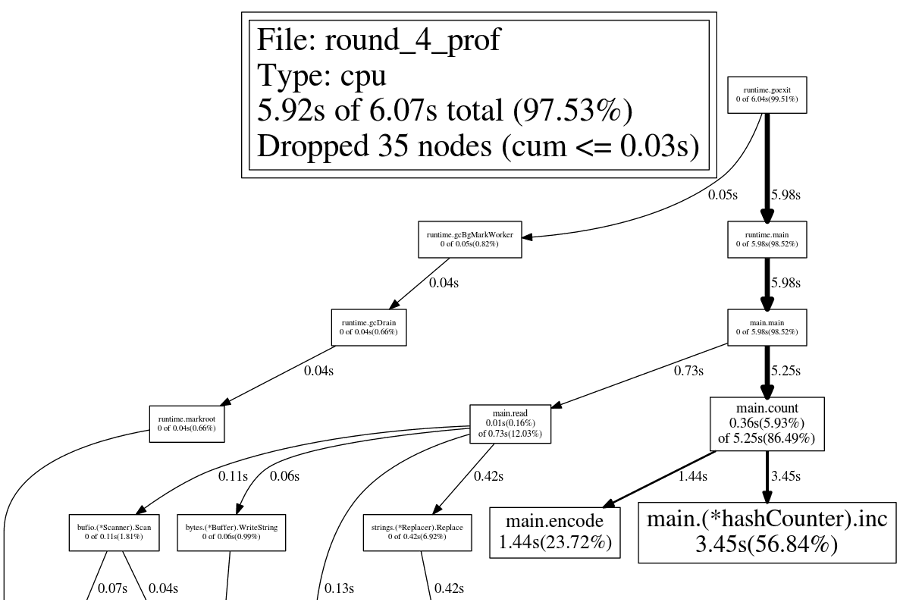

Round 4: Faster Maps

Many languages (Java and Python to name two) allow you to use custom hash functions; this can be used to increase map performance in special cases. Go does not allow for custom hash functions — you can hear more about that in Keith Randall's Gophercon talk about maps: hash functions are "hard to get right", so "Go gets it right for you."

I don't disagree with that assessment. Go maps are simple and mostly just do what I want. I shouldn't need to fiddle with anything. However, sometimes we just wanna go fast. While we can't customize Go's built-in maps, we can always implement our own. To keep the implementation work to a minimum, let's make a hash counter with the following features:

- a fixed table size

- collision resolution via separate chaining with linked lists

- a hash function that is just the input modulo the table size

- only two methods:

incto increment a value in the counter, andgetto fetch a count

The version with a custom hash counter runs in about 6.2 seconds.

package main

import (

"bufio"

"bytes"

"fmt"

"os"

"strings"

)

var toNum = strings.NewReplacer(

"A", string(0),

"C", string(1),

"G", string(2),

"T", string(3),

)

const hashSize = 1 << 18

func hash(key uint64) int {

return int(key) % hashSize

}

type entry struct {

key uint64

value int

next *entry

}

type hashCounter struct {

entries [hashSize]*entry

}

func (hc *hashCounter) get(key uint64) int {

for e := hc.entries[hash(key)]; e != nil; e = e.next {

if e.key == key {

return e.value

}

}

return 0

}

func (hc *hashCounter) inc(k uint64) {

h := hash(k)

p := &hc.entries[h]

for e := *p; e != nil; e = e.next {

if e.key == k {

e.value++

return

}

}

e := &entry{k, 1, nil}

if *p == nil {

*p = e

} else {

e.next = *p

*p = e

}

}

func main() {

sequence := "GGTATTTTAATTTATAGT"

dna := read()

counts := count(dna, len(sequence))

seqCount := counts.get(encode([]byte(toNum.Replace(sequence))))

fmt.Printf("%v\t%v\n", seqCount, sequence)

}

func read() []byte {

var buf bytes.Buffer

scanner := bufio.NewScanner(os.Stdin)

for scanner.Scan() {

buf.WriteString(toNum.Replace(scanner.Text()))

}

return buf.Bytes()

}

func count(dna []byte, length int) (counts hashCounter) {

for i := 0; i < len(dna)-length+1; i++ {

key := encode(dna[i : i+length])

counts.inc(key)

}

return

}

func encode(sequence []byte) uint64 {

var num uint64

for _, char := range sequence {

num = (num << 2) | uint64(char)

}

return num

}

Conclusion

Starting from a straightforward implementation, using Go's profiling tools helped us to improve the speed by about 4x. I'm sure there are plenty more small changes that could further improve the performance, but this post is too long already!

By mostly following the approach outlined here, I was able to speed up the k-nucleotide benchmark for Go by over 2x, from 55 seconds to 24. For a short while, this was the fastest Go version. Since then, many more improvements have been made, bringing it down to 16 seconds.